3 Ways To Improve Your Large Language Model

Enhancing the power of Llama 2

Large Language Models (LLMs) are here to stay. With the recent release of Llama 2, LLMs are approaching the performance of ChatGPT and with proper tuning can even exceed it.

Using these LLMs is often not as straightforward as it seems especially if you want to fine-tune the LLM to your specific use case.

In this article, we will go through 3 of the most common methods for improving the performance of any LLM:

Prompt Engineering

Retrieval Augmented Generation (RAG)

Parameter Efficient Fine-Tuning (PEFT)

There are many more methods but these are the easiest and can result in major improvements without much work.

These 3 methods start from the least complex method, the so-called low-hanging fruits, to one of the more complex methods for improving your LLM.

To get the most out of LLMs, you can even combine all three methods!

Before we get started, here is a more in-depth overview of the methods for easier reference:

You can also follow along with the Google Colab Notebook to make sure everything works as intended.

Load Llama 2 🦙

Before we get started, we need to load in an LLM to use throughout these examples. We’re going with the base Llama 2 as it shows incredible performance and because I am a big fan of sticking with foundation models in tutorials.

We will first need to accept the license before we can get started. Follow these steps:

After doing so, we can log in with our HuggingFace credentials so that this environment knows we have permission to download the Llama 2 model that we are interested in:

from huggingface_hub import notebook_login

notebook_login()Next, we can load in the 13B variant of Llama 2:

from torch import cuda, bfloat16

import transformers

model_id = 'meta-llama/Llama-2-13b-chat-hf'

# 4-bit Quanityzation to load Llama 2 with less GPU memory

bnb_config = transformers.BitsAndBytesConfig(

load_in_4bit=True,

bnb_4bit_quant_type='nf4',

bnb_4bit_use_double_quant=True,

bnb_4bit_compute_dtype=bfloat16

)

# Llama 2 Tokenizer

tokenizer = transformers.AutoTokenizer.from_pretrained(model_id)

# Llama 2 Model

model = transformers.AutoModelForCausalLM.from_pretrained(

model_id,

trust_remote_code=True,

quantization_config=bnb_config,

device_map='auto',

)

model.eval()

# Our text generator

generator = transformers.pipeline(

model=model, tokenizer=tokenizer,

task='text-generation',

temperature=0.1,

max_new_tokens=500,

repetition_penalty=1.1

)Most open-source LLMs have some sort of template that you must adhere to when creating prompts. In the case of Llama 2, the following helps guide the prompts:

This means that we would have to use the prompt as follows to generate text properly:

basic_prompt = """

<s>[INST] <<SYS>>

You are a helpful assistant

<</SYS>>

What is 1 + 1? [/INST]

"""

print(generator(basic_prompt)[0]["generated_text"])Which generates the following output:

"""

Oh my, that's a simple one!

The answer to 1 + 1 is... (drumroll please)... 2! 😄

"""What a cheeky LLM!

The template is less complex than it seems but with a bit of practice, you should get it right in no time.

Now, let’s dive into our first method for improving the output of an LLM, prompt engineering.

1. Prompt Engineering ⚙️

How we ask the LLM something has a major effect on the quality of the output that we get. We need to be precise, complete and give examples of the output we are interested in.

This tailoring of your prompt is called prompt engineering.

Prompt engineering is such an amazing way to “tune” your model. It requires no updating of the model and you can quickly iterate over it.

There are two major concepts in prompt engineering:

Example-based

Thought-based

Example-based Prompt Engineering

In example-based prompting, such as one-shot or few-shot learning, we provide the LLM with a couple of examples of what we are looking for.

This generally generates text that is more aligned with how we want it.

For example, let’s apply sentiment classification to a short review:

prompt = """

<s>[INST] <<SYS>>

You are a helpful assistant.

<</SYS>>

Classify the text into neutral, negative or positive.

Text: I think the food was okay. [/INST]

"""

print(generator(prompt)[0]["generated_text"])Which generates the following output:

"""

Positive. The word "okay" is a mildly positive word,

indicating that the food was satisfactory or acceptable.

"""Personally, I am not that convinced with the answer. I think it is more neutral than positive. Also, we have to search in the text for the answer.

Instead, let’s give it an example of how we want the answer to be generated:

prompt = """

<s>[INST] <<SYS>>

You are a helpful assistant.

<</SYS>>

Classify the text into neutral, negative or positive.

Text: I think the food was alright.

Sentiment:

[/INST]

Neutral</s><s>

[INST]

Classify the text into neutral, negative or positive.

Text: I think the food was okay.

Sentiment:

[/INST]

"""

print(generator(prompt)[0]["generated_text"])When we look at the output, we get the expected result:

"""

Neutral

"""Now, the LLM is to the point and gives only the answer that we are interested in. Much better!

Thought-based Prompt Engineering

We can go a step further and ask the LLM to “reason” about its answer.

By having the LLM divide its thinking into smaller steps, it allows for more computation to be given to each step. These smaller steps are generally referred to as the “thoughts” of the LLM.

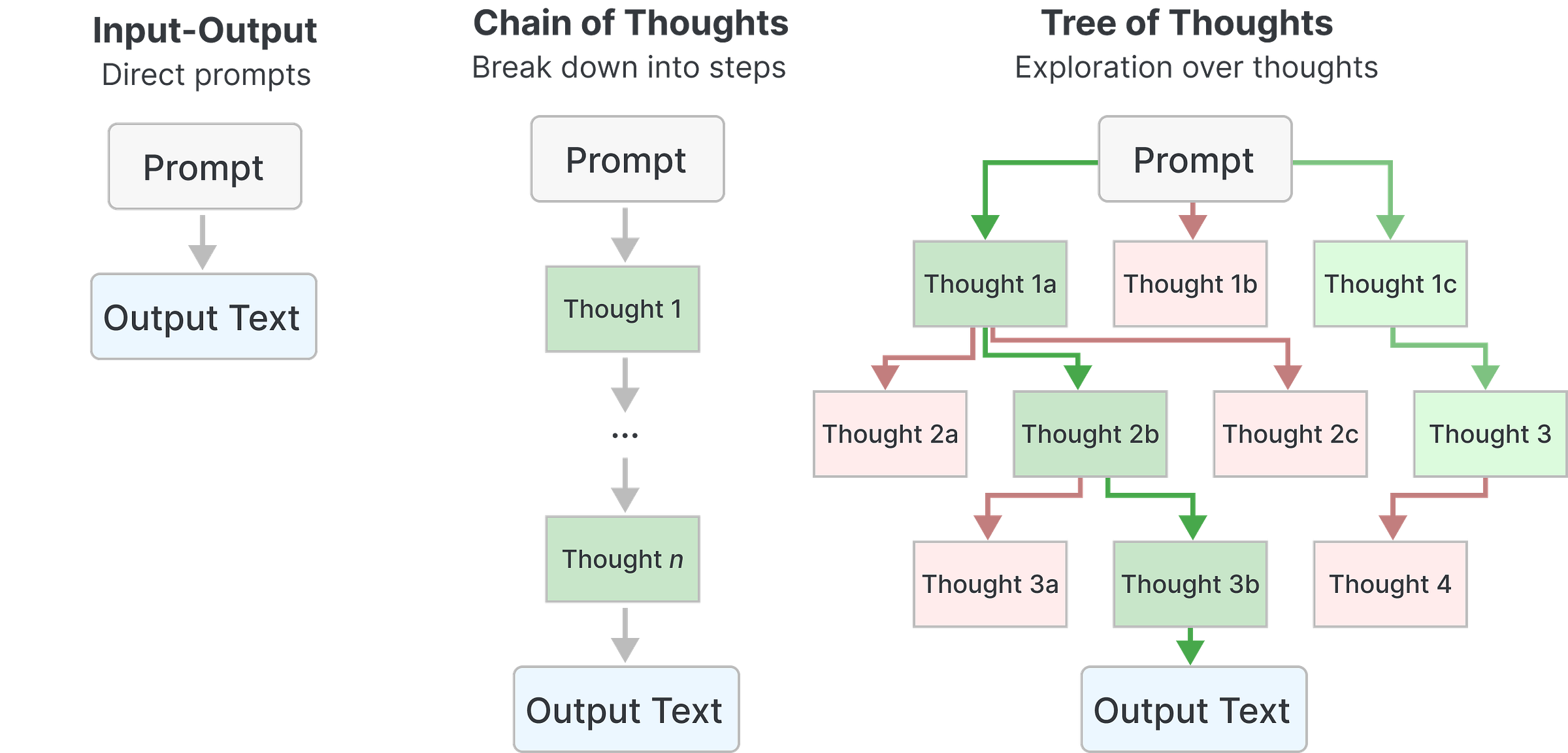

There are many ways that we can use thought-based prompting and we can make it quite complex as seen below:

However, let’s start with the most basic example. What if we ask the model to solve a problem by breaking the problem into steps?

prompt = """

<s>[INST] <<SYS>>

You are a helpful assistant.

<</SYS>>

Do the odd numbers in this group add up to an even number? 3, 5, 15, 32.

Solve by breaking the problem into steps.

Identify the odd numbers, add them, and indicate whether the result is odd or even.[/INST]

"""

print(generator(prompt)[0]["generated_text"])The output we get shows its reasoning in detail:

"""

Hello! I'd be happy to help you with that. Let's break down the problem into steps:

Step 1: Identify the odd numbers in the group.

The odd numbers in the group are:

3, 5, 15

Step 2: Add the odd numbers.

3 + 5 + 15 = 23

Step 3: Is the result odd or even?

23 is an odd number.

Therefore, the sum of the odd numbers in the group is an odd number.

"""As we have seen before, this is also called Chain-of-Thought where the LLM has a sequence of individual thoughts or steps it follows.

These individual steps also help the model to stay accountable during its computation. Because it has “reasoned” about each step individually there is structure in its “thinking” process.

2. Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) 🗃️

Although prompt engineering can get us an improvement, it cannot make the LLM know something it has not learned before.

When an LLM is trained in 2022, it has no knowledge about what has happened in 2023.

This is where Retrieval-Augmented Generation (RAG) comes in. It is a method of providing external knowledge to an LLM that it can leverage.

In RAG, a knowledge base, like Wikipedia, is converted to numerical representations to capture its meaning, called embeddings. These embeddings are stored in a vector database so that the information can easily be retrieved.

Then, when you give the LLM a certain prompt, the vector database is searched for information that relates to the prompt.

The most relevant information is then passed to the LLM as the additional context that it can use to derive its response.

In practice, RAG helps the LLM to “look up” information in its external knowledge base to improve its response.

Creating a RAG Pipeline with LangChain

To create an RAG pipeline or system, we can use the well-known and easy-to-use framework called LangChain.

We’ll start with creating a tiny knowledge base about Llama 2 and writing it into a text file:

# Our tiny knowledge base

knowledge_base = [

"On July 18, 2023, in partnership with Microsoft, Meta announced LLaMA-2, the next generation of LLaMA." ,

"Llama 2, a collection of pretrained and fine-tuned large language models (LLMs) ",

"The fine-tuned LLMs, called Llama 2-Chat, are optimized for dialogue use cases.",

"Meta trained and released LLaMA-2 in three model sizes: 7, 13, and 70 billion parameters.",

"The model architecture remains largely unchanged from that of LLaMA-1 models, but 40% more data was used to train the foundational models.",

"The accompanying preprint also mentions a model with 34B parameters that might be released in the future upon satisfying safety targets."

]

with open(r'knowledge_base.txt', 'w') as fp:

fp.write('\n'.join(knowledge_base))After doing so, we will need to create an embedding model that can convert text to numerical representations, namely embeddings.

We will choose a well-known sentence-transformers model, namely sentence-transformers/all-MiniLM-L6-v2.

🔥 TIP 🔥 You can find an amazing list of models at the Massive Text Embedding Benchmark (MTEB) Leaderboard.

from langchain.embeddings.huggingface import HuggingFaceEmbeddings

# Embedding Model for converting text to numerical representations

embedding_model = HuggingFaceEmbeddings(

model_name='sentence-transformers/all-MiniLM-L6-v2'

)Now that we have an embedding model and a tiny knowledge base, we can start developing our vector database. There are many to choose from but let’s choose one that we can use locally, namely FAISS.

🔥 TIP 🔥 Other great vector databases are Pinecone and Weaviate.

from langchain.text_splitter import CharacterTextSplitter

from langchain.vectorstores import FAISS

from langchain.document_loaders import TextLoader

# Load documents and split them

documents = TextLoader("knowledge_base.txt").load()

text_splitter = CharacterTextSplitter(chunk_size=1000, chunk_overlap=0)

docs = text_splitter.split_documents(documents)

# Create local vector database

db = FAISS.from_documents(docs, embedding_model)The db variable contains everything we need for the database but still need to combine it with an LLM. LangChain makes this incredibly easy and straightforward:

from langchain.chains import RetrievalQA

from langchain.llms import HuggingFacePipeline

# Load LLM into LangChain

llm = HuggingFacePipeline(pipeline=generator)

# RAG Pipeline

rag = RetrievalQA.from_chain_type(

llm=llm, chain_type='stuff',

retriever=db.as_retriever()

)The great thing about the two variables llm and rag that we created is that we can use llm to do some prompting without the RAG pipeline and rag with the RAG pipeline.

Let’s start without RAG. What happens if we ask the LLM about itself, Llama 2?

>>> llm('What is Llama 2?')

"""

Llama 2 is a cryptocurrency that was created as a parody of the popular cryptocurrency Dogecoin. It was designed to be a more serious and less meme-focused alternative to Dogecoin, with a focus on privacy and security.

Llama 2 uses a proof-of-work consensus algorithm and has a block time of 1 minute. It also features a decentralized governance system that allows holders of the llama2 token to vote on proposals for the development and growth of the project.

One of the key features of Llama 2 is its use of "ring signatures" to enhance privacy and security. Ring signatures are a type of digital signature that can be used to hide the identity of the sender in a transaction. This makes it more difficult for hackers or other malicious actors to trace the source of a transaction.

Overall, Llama 2 is a privacy-focused cryptocurrency that is designed to provide users with greater control over their financial data and more secure transactions.

"""

Cryptocurrency? That is not exactly the answer that we were looking for… It seems that it has no knowledge about itself.

Let’s try to use the RAG pipeline instead:

>>> rag('What is Llama 2?')

"""

Llama 2 is a collection of pretrained and fine-tuned large language models

(LLMs) announced by Meta in partnership with Microsoft on July 18, 2023.

"""That is much better!

Since we have given it external knowledge about Llama 2, it can leverage that information to generate more accurate answers.

🔥 TIP 🔥 Prompting can get difficult and complex quite quickly. If you want to know the exact prompt that is given to the LLM, you can run the following before running the LLM:

import langchain

langchain.debug = True3. Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning 🛠️

Both prompt engineering and RAG generally do not change the LLM in itself. Its parameters remain the same and the model does not “learn” anything new, it simply leverages.

We can fine-tune the LLM for a specific use case with domain-specific data so that it learns something new.

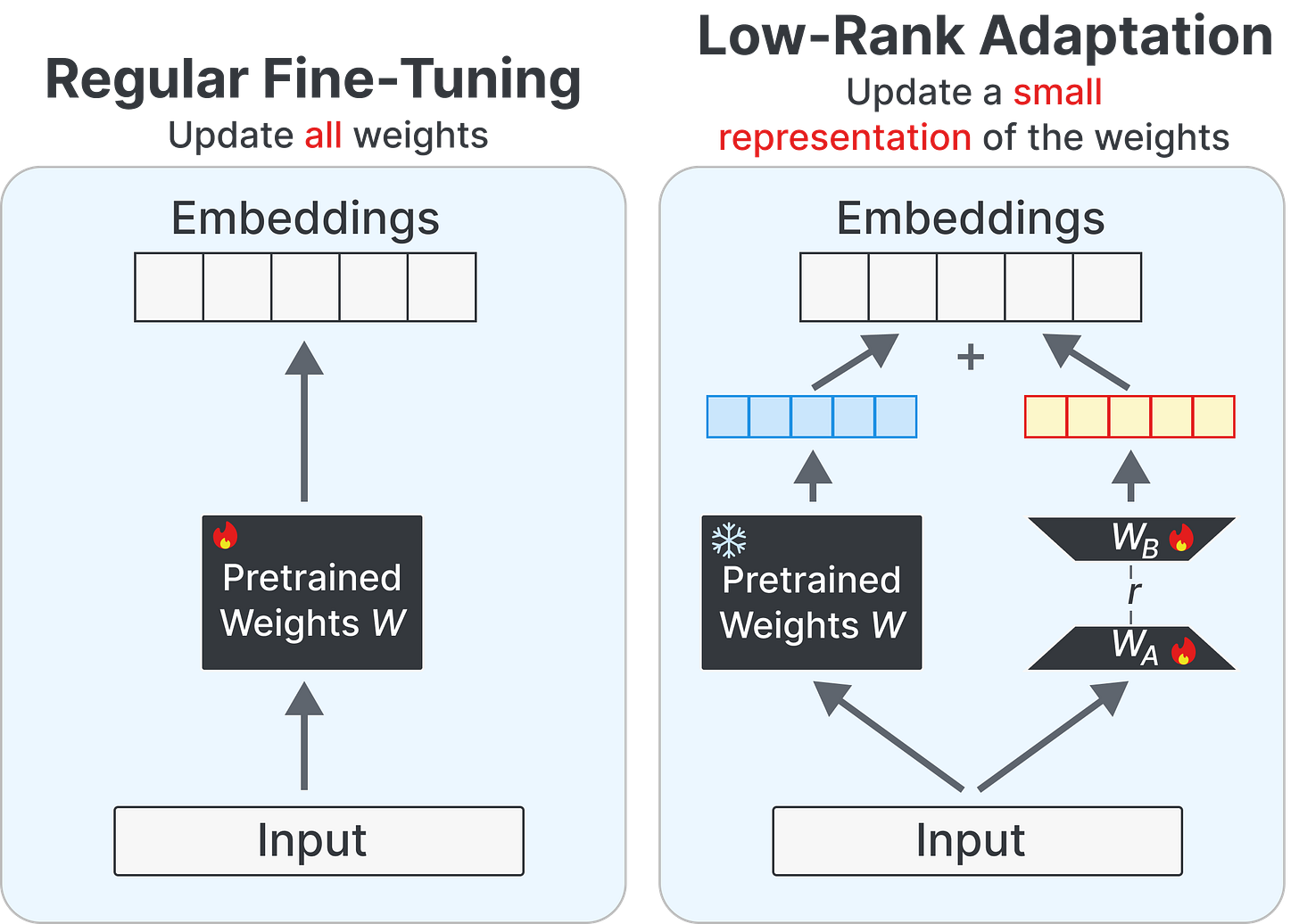

Instead of fine-tuning the model’s billions of parameters, we can leverage PEFT instead, Parameter-Efficient Fine-Tuning. As the name implies, it is a subfield that focuses on efficiently fine-tuning an LLM with as few parameters as possible.

One of the most often used methods to do so is called Low-Rank Adaptation (LoRA). LoRA finds a small subset of the original parameters to train without having to touch the base model.

These parameters can be seen as smaller representations of the full model where only the most important or impactful parameters are trained. The beauty is that the resulting weights can be added to the base model and therefore saved separately.

Fine-Tuning Llama 2 with AutoTrain

The process of fine-tuning Llama 2 can be difficult with the many parameters out there. Fortunately, AutoTrain takes most of the difficulty away from you and allows you to fine-tune in only a single line!

We’ll start with the data. As always, it is the one thing that affects the resulting performance most!

We are going to make the base Llama 2 model, a chat model, and we will use the OpenAssistant Guanaco dataset for that:

import pandas as pd

from datasets import load_dataset

# Load dataset in pandas

dataset = load_dataset("timdettmers/openassistant-guanaco")

df = pd.DataFrame(dataset["train"][:1000]).dropna()

df.to_csv("train.csv")This dataset has a number of question/response schemes that you can train Llama 2 on. It differentiates the user with the ### Human tag and the response from the LLM with the ### Assistant tag.

We are only going to take 1000 samples from this dataset for illustration purposes but the performance will definitely increase with more quality data points.

NOTE: The dataset will need a text column which is what AutoTrain will automatically use.

The training in itself is extremely straightforward after installing AutoTrain with only a single line of code:

autotrain llm --train \

--project_name Llama-Chat \

--model abhishek/llama-2-7b-hf-small-shards \

--data_path . \

--use_peft \

--use_int4 \

--learning_rate 2e-4 \

--num_train_epochs 1 \

--trainer sft \

--merge_adapterThere are a number of parameters that are important:

data_path: The path to your data. We saved a train.csv locally with a text column that AutoTrain will use during training.model: The base model that we are going to fine-tune. It is a sharded version of the base model that allows for easier training.use_peft&use_int4: The parameters enable the efficient fine-tuning of the model which reduces the VRAM that is necessary. It leverages, in part, LoRA.merge_adapter: To make it easier to use the model, we will merge the LoRA together with the base model to create a new model.

When you run the training code, you should get an output like the following:

And that is it! Fine-tuning a Llama 2 model this way is incredibly easy and since we merged the LoRA weights with the original model, you can load in the updated model as we did before.

🔥 TIP 🔥 Although fine-tuning in one line is amazing, it is very much advised to go through the parameters yourself. Learning what it exactly means to fine-tune with in-depth guides helps you also understand when things are going wrong.

Thank you for reading!

If you are, like me, passionate about AI and/or Psychology, please feel free to add me on LinkedIn, follow me on Twitter, or subscribe to my Newsletter. You can also find some of my content on my Personal Website.

Update: I uploaded a video version to YouTube that goes more in-depth into how to use these methods:

Love your content! It's very clearly explained and easy to follow along. I've sent a connection request on LinkedIn and subscribed to your YouTube channel :-)